The Women in Construction 2022 keynote address: The value of gender diversity to the industry

March 11, 2022

By

Canadian Consulting Engineer

As a long-time engineer and then president of a major engineering firm, I’ve spent my fair share of time on construction sites. From crane operators to construction supervisors, I’ve witnessed first-hand the biases and prejudices this sector can have towards women. However, I’ve also seen how women can thrive and flourish in this industry.

In fact, I believe there has never been a better time to close the gender gap in construction. And there’s no better backdrop to discuss these issues than International Women’s Day.

Some people still ask, “Why do we celebrate International Women’s Day?” “Why do we have women-specific events?” “Why do we have ‘women in construction’ conferences?”

There are many reasons, yet the most glaring is that despite some progress in certain areas, gender equity remains elusive. This is particularly true in the construction industry and engineering as a whole.

The challenges of achieving equity

According to BuildForce Canada’s 2021 Construction and Maintenance Looking Forward report, only about 5% of tradespeople working on construction sites are women. This number rises to about 13% when looking at the entire construction industry, which includes administrative roles.

Out of about 1.5 million construction workers nationwide, only about 190,000 are women. This number has changed very little over the past few decades.

While many women can have rewarding careers in construction, many face discrimination and can be made to feel unwelcome. So we hold ‘women in construction’ conferences to address some of these issues, to raise awareness, to build solidarity and to inspire women to join this industry.

We celebrate International Women’s Day because for most of history, women have not been celebrated—or even acknowledged. In fact, for thousands of years, most women had little or no control over their lives.

Women still do not have equality.

Women had no access to education, no decisions to make about careers and, in many cases, no control over whom they would marry. This was the reality for most women who ever lived, until quite recently—and sadly, it remains the reality for millions of women and girls around the world.

It is important to highlight in Canada, women still do not have equality—and that inequality is greater for Black, Indigenous and women of colour. In the end, we have a long way to go before having a truly equal, diverse and inclusive society.

If the past few years have taught us anything, it should be that progress is not guaranteed. We are living in a period of great political, social and economic uncertainty. A resurgence of ignorance and intolerance is sweeping across many Western countries. Fights we thought were won years ago are being dragged back into the spotlight.

This is why we cannot be complacent. This is why we need to continue to advocate and fight for equality. But despite some setbacks, I believe we are making forward progress.

I believe the future is bright. A big reason is the efforts of countless organizations and individuals committed to fighting for equality.

My own story

Since I sold my engineering firm and retired in 2016, I have been committed to helping build a more inclusive, diverse and equal future, particularly in engineering and other traditionally male-dominated fields. As a woman and an immigrant, this is a subject that is close to my heart.

I came to Montreal from Iran during the revolution in 1979. I had just completed my undergraduate degree in engineering from a top school. My dream was to complete my master’s and PhD, but I had only $2,000 to my name.

My late brother, Mahmoud, had just completed his bachelor’s in engineering at Concordia University. I was to be enrolled at another university, but had no way of paying the tuition. He convinced me to meet one of his professors, Cedric Marsh.

After a one-hour meeting, Marsh said to me, “Come to Concordia. Why would you go anywhere else? We’ll give you financial support.”

That day, Professor Marsh and Concordia changed my life. I completed my master’s degree and then in 1989 became the first woman awarded a PhD from Concordia’s building engineering program.

I was often the only woman in the room.

During my academic experience and professional career, I was often the only woman in the room. Unfortunately, I’m sure some of you can relate to that.

I remember attending a conference in Toronto where I was the only woman among 700 attendees. The emcee began his introduction with “Lady and gentlemen.”

My drive to rise to the highest academic and professional levels was in large part thanks to my parents. I grew up with three brothers, all engineers, and one sister, who became a dentist. My father owned an all-boys high school. He made sure I was always comfortable in traditionally male environments.

During summers, my father had me teach classes in his school — to boys who were 14 to 16 years old. I remember my father saying to me, “If you can handle boys that age, you can handle anyone.” That has certainly proven to be true.

Like my father, my mother was ahead of her time. She was a housewife who married young and never finished high school, yet she understood the importance and value of education, especially for her daughters.

I clearly remember her words to me and my sister when we were young: “The only way to be independent as women is through education.” My mother was an exceptional woman and she was wright: education is the great equalizer.

Education is the most effective way to achieve social mobility. It can also help overcome various forms of discrimination, including racism and sexism.

Education is the great equalizer.

When I was president of my engineering firm, my assistant would often transfer calls to me from men looking to speak to the boss. When I answered, they would again ask for the boss, to which I would reply, “I am the boss.”

Sometimes they would still sound doubtful, so I would say, “I have a PhD in building engineering, how can I help you?” That almost always got their attention, if not their respect.

The point wasn’t that they were doubting my education; they were doubting my competency as a woman.

The labour deficit and the fourth industrial revolution

While things are changing, we still have a lot of ground to cover, but there’s never been a better time for women to embark on careers in the construction industry. According to the BuildForce Canada report, the country could be facing a deficit of more than 80,000 construction workers by 2030.

This is also true in the engineering sector. According to Engineers Canada, we could be short as many as 100,000 engineers in the next few years, due to an aging population of experienced professionals set to retire—people like me—and projected demand for more engineers.

This could be very damaging for Canada’s economy and long-term prosperity. Attracting more women is one key strategy to cutting into this labour deficit. The world is in the midst of its fourth industrial revolution and we cannot afford to leave nearly half our workforce behind.

Previous industrial revolutions were about advances in technology, such as:

- The invention of steam power, the railway and machine manufacturing.

- The advent of electric power and petroleum fuel.

- The rise of telecommunications and computers.

The fourth revolution is about connectivity between existing, evolving and new technologies. We see this in the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), advanced manufacturing, smart cities and much more.

This revolution relies not on physical labour and strength, but on innovation and design through highly technical skills and knowledge. In other words, it relies on skilled workers and technology.

Implications of technology

Tech and engineering companies are imagining, designing and creating how the future will look, feel and sound. So what happens if the people building the world of tomorrow represent only the majority? Everyone else is left behind.

Technology can connect, bridge divides and open new lines of communication, but it can also restrict and censor. It can create echo chambers and silos of thoughts and ideas. We all have a different relationship to technology. We use and have access to technology in very different ways.

A study published in 2019 in The Washington Post and The Guardian found safety features in cars are designed for men. The crash-test dummies used to assess a vehicle’s safety features are based on the size of the average male. This leads to women being nearly 50% more likely to be seriously injured and more than 70% more likely to suffer minor injuries in a crash than men.

This holds true even though men are more likely to be involved in an accident. Why? Because the safety features were designed by men for men. From the height of the seatbelts to the positioning and strength of the airbags, everything is calibrated for men.

We have heard examples of AI taking on the biases of its programmers and learning bad behaviour. There is the case of Compas, a computer program used by courts in the U.S. to flag defendants who were likely to reoffend. An investigative report by ProPublica found, under this system, Black defendants were wrongly identified at nearly twice the rate of white defendants, making a notoriously discriminatory justice system even more so.

Everything is calibrated for men.

A recent study by the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) found a majority of face recognition algorithms in use are racist. The study showed Asian, African-American or Indigenous faces resulted in much higher false-positive matches than Caucasian faces, by a factor of 10 or 100 times. This matters because law enforcement increasingly relies on this technology to identify criminals or security threats, which means visible minorities are far more likely to be falsely arrested or detained than white people.

Many of these biases and oversights aren’t intentional, but as they say, you don’t know what you don’t know. It’s critical that every group gets a proportional voice at the table.

Whether it’s a construction firm or a team of software engineers, the people shaping our society need to be representative of the people living in our society—something that sadly is not the case here in Canada and in most of the world.

Diversity and profit

The studies on diversity are clear. Companies that are more diverse, equal and inclusive are significantly more competitive and profitable.

A report by McKinsey & Company found companies with greater gender diversity in executive positions were up to 21% more profitable than their male-dominated counterparts. Those with greater ethnic diversity were up to 33% more profitable than less diverse competitors. Promoting diversity and equality isn’t just morally and ethically right—it’s smart business.

Ongoing setbacks

The conditions for achieving gender equity have never been better, yet the ongoing pandemic has the potential to set women back. With many school and daycare closures, some couples were faced with the difficult decision of having one parent be the primary caregiver while the other worked.

Data from Statistics Canada show women spend more than twice as much time on child care in a couple as men do. They also spend 40% more time on household chores than men. Women are more likely to put their careers on hold to care for their children and, even if they don’t quit their jobs, their performance is more likely to be adversely affected.

A 2020 McKinsey & Company report estimated COVID-19 could set women back at least half a decade. Based on a survey of 40,000 Americans, one in four women were contemplating downshifting their careers or leaving the workforce completely. This was an American study, but based on the statistics I mentioned from StatsCan, it’s likely there is a similar pattern emerging here.

The key factor is many women are pulling double shifts. They are being forced to choose between their children and their careers. So my message to men is: be better allies to women. At home, be better partners. At work, be better colleagues.

The main issue women have entering male-dominated fields isn’t that there aren’t any other women. It isn’t that women are inherently uninterested in those fields. The issue is these environments are often actively hostile to women. Whenever women have “trespassed” on traditionally male territory, they have been made unwelcome.

The issue is work environments that are actively hostile to women.

While less than 13% of working engineers are women, more than 20% of engineering graduates are women. Why do we see such a big drop between those who graduate and those who work in engineering? Because women can be made to feel unwelcome or disrespected.

When doing internships in male-dominated fields, young women are often not taken seriously. They frequently endure inappropriate comments and behaviours and, in some cases, face open hostility from men.

By the time they get their degree, they are already disillusioned. And if they aren’t, these same behaviours are waiting for them when they enter the workforce. Is it any wonder women often choose to change careers, rather than face that every day?

Improving the field

Women don’t need special treatment; we just need a level playing field.

My hope for 2022 is we can come together and help make the field just little more level. Don’t underestimate the importance and significance of your role. Each of us has the power to make a difference.

As the famous Persian poet Rumi said, “You are not a drop in the ocean, you are the entire ocean in a drop.” So, be the changemaker!

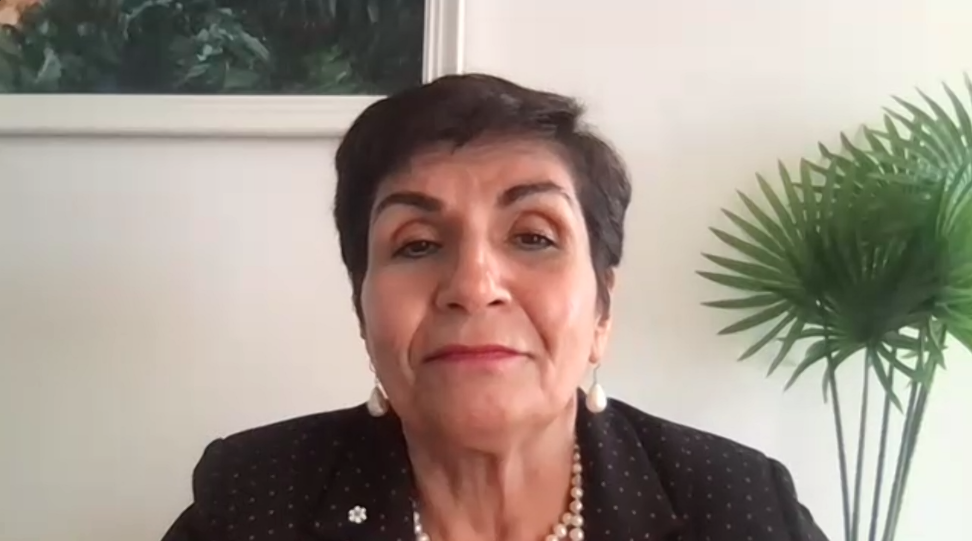

Gina Parvaneh Cody delivered this keynote address at the second annual Women In Construction Virtual Event on Mar. 10. For more about the event, visit www.rocktoroad.com/virtual-events/women-in-construction-2022.